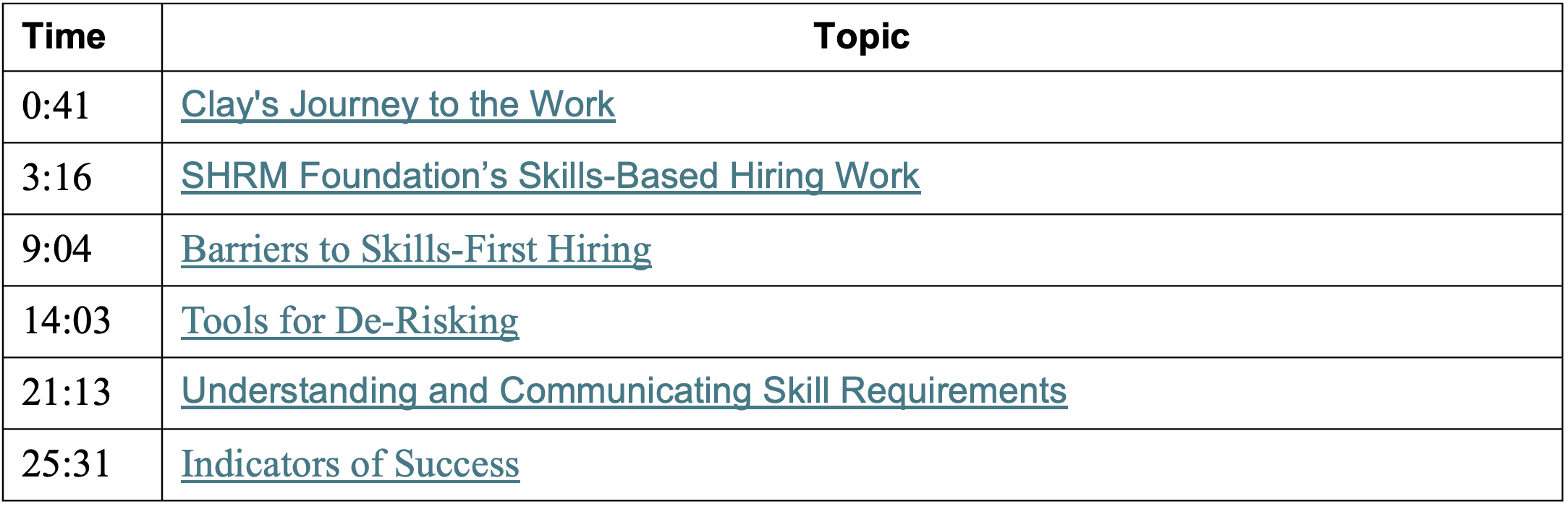

Oct 07 2024 30 mins 1

Clayton Lord of the SHRM Foundation joined me to discuss shifting from a degree-centric hiring system to one that is skills-based. We talked about how the Foundation is helping employers operationalize this transition, the benefits it accrues to candidates and businesses, and the risks and challenges being addressed to spread its benefits on a broader scale.

Michael Horn:

Welcome to the Future of Education, where we are dedicated to building a world in which all individuals can build their passions, fulfill their potential, and live a life of purpose. To help us think through that today, I'm tremendously excited. We have Clay Lord, he's the Director of Foundation Programs at SHRM, joining us to think about how we help unlock that path of progress for individuals, employees, and their jobs, but also for employers who can get so much more out of those individuals when there's a better match in all facets of how they work with each other. So, Clay, thank you so much for joining us today.

Clayton Lord:

Of course. Thanks for having me.

Clay's Journey to the Work

Michael Horn:

Yeah, no, you bet. Your work obviously gets to interact with lots of different individuals, lots of different companies, creating changes in a variety of ways. But just before we dive into that, talk us through your own path to the role you're in now and your passion for it, and how you got to know SHRM originally.

Clayton Lord:

You know, it's an interesting and sort of circuitous story. I've been at the SHRM Foundation for about 18 months now. Prior to that, for about 20 years, I was in the arts and culture sector, working at the local level and then at the national level on a variety of issues that I would now roll up together as workforce issues for the cultural sector in the United States. This sector mirrors a lot of the populations that we work on now at the SHRM Foundation, in that it is generally speaking, chronically economically insecure. It's extremely diverse. It doesn't have the strongest voice as a class when it comes to policy.

I came out of Georgetown. I grew up with a lot of privilege, went to a really good college, and dove into the cultural sector. Through a lot of engagement with different partners, I developed my understanding of what equity meant and my understanding of how I got to where I was and where that was me and where that was the conditions that I was given at birth.

Since then, I've tried to devote a lot of my work and my life to increasing opportunity for folks who are otherwise left out in the cold because they don't work within the same systems or don't have the same advantages as some people do. I ended up at SHRM because I knew some folks who were working there. SHRM is the largest society for HR professionals in the world, with 340,000 employer members predominantly in the United States. The SHRM Foundation is one of the only real loci for driving employer action, particularly through the HR function, to be agents for social good. It seemed like an interesting fit for me as I was trying to navigate from the niche work in arts and culture into broader conversations about workforce and the future of work.

SHRM Foundation’s Skills-Based Hiring Work

The Future of Education is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Michael Horn:

Super interesting to hear that pathway, and I love how it's not linear and yet ends up in a place of passion for you. On that topic, over the next decade, you all have set a lofty goal of aiming to transform hiring and advancement practices for 100,000 employers, 500,000 HR professionals, managers, executives, and specifically as part of that, your aim is to shift away from a degree-centric hiring model toward a skills-first model. I'd love for you to talk through what that would look like when it's done and why it matters so much.

Clayton Lord:

Well, it's a great question. The short answer is that it is responsive to the evolutions in how people are being educated and how they're trying to find their way into work. Today, two in three working-age adults in the United States do not have a four-year degree. Yet, three in four job postings require a four-year degree when they're posted. This represents a significant and ongoing mismatch between where and how people are finding their skills, aptitudes, and competencies, where they're developing the things that they can bring to bear in the workplace, and what is required as a first gateway to access a lot of jobs.

Among three focuses that the SHRM Foundation has, one of them is what we call widening pathways to work. It's focused on two sides of that coin. One is around untapped pools, helping employers understand where, when, and how to engage folks who have historically been marginalized out of the job market, including people with disabilities, people who've been justice impacted, people connected to the military, older workers, and opportunity youth (people aged 16 to 24 who don't work or go to school).

On the other side of that coin is skills-first at work. We focus on helping employers shift their hiring and retention practices from being degree-centric to embracing a broader aperture of hiring and advancement that we shorthand as skills-first. This is not to the exclusion of degrees. It's to say that people get skills in all sorts of ways, at various moments in their lives. If they're doing it right, they're learning new skills every single day. All of those skills deserve to be taken into account when you're hiring for a job, which is essentially a bundle of skills.

At the SHRM Foundation, we are making that investment by creating the conditions to help employers, 90% of whom today say adopting skills-first strategies is a good idea, but only 15% of whom are actually saying they're doing anything about it. We aim to move them from agreement to action by offering incremental, measurable, manageable opportunities for change, allowing them to move towards a skills-first mentality that lets them access the full spectrum of talent.

You asked what that looks like. In ten years, if we do it right, we will hit what we think is an inevitable tipping point. Skills-first is the future, whether we do anything about it or not. Those who think we aren't moving towards more people accumulating skills outside of a four-year institution will be left behind. However, we believe there's a way to handle this transition that is less chaotic and more manageable for the world of work.

For us, if we get to that moment, we will have 100,000 employers who have demonstrated that they've moved in the direction of skills-first hiring. We don't think it's flipping a switch, but we will build maturity models to test how employers are doing and how much they've embraced these practices. There are nearly 3 million HR professionals and millions more who touch the hiring function every year. Even a small percentage of those, which we tag at 500,000 HR professionals, hiring managers, and C-suite folks, educated on skills-first hiring and advancement practices, would create a tipping point. Our goal is that skills-first hiring becomes ubiquitous and unremarkable, the default practice that happens all around us. Right now, the default is degree-centered, leaving many people out. Changing the paradigm to hire for the full spectrum of skills, regardless of where, when, or how they were acquired, will open up more opportunities for people and provide workplaces with the full spectrum of talent.

This edition of the Future of Education is sponsored by:

Barriers to Skills-First Hiring

Michael Horn:

It strikes me that you want employers and companies to hire people who will help them progress, recognizing individuals not just as a bundle of credentials but through the collection of their experiences. This alignment benefits both the employer and the employee, who get to make progress in their lives by matching their capabilities and drives. You started to allude to it; this isn't a switch that you can just flip. What are the big barriers toward moving toward this vision that you see right now?

Clayton Lord:

In our research, there are three main barriers to moving from degrees to skills.

The first is the ROI being murky. The return on investment for a degree-centered practice is relatively well known. Sometimes it works out well, sometimes poorly, but when it works out poorly, the blame is usually placed on the candidate, not the business or HR provider. If you hire five people from Ivy League schools and two of them don't work out, the assumption is that something didn't work out with those two people. If you hire five people from skills-based backgrounds without a degree and two of them don't work out, the assumption is that the HR professional or hiring manager took too big a risk.

The second barrier is around trust, quality, and knowledge. There are about 60,000 providers of credentials in the world and over a million credential options, many of them of dubious quality. There is also an ever-growing number of startups and vendors in this space. Pair that with the fact that knowing how to move from degrees to skills is different from believing that moving from degrees to skills is a good idea, and you have a challenge, particularly for small to mid-size employers.

The third barrier is risk aversion and loneliness. Businesses are naturally risk-averse. When you ask them to take a leap into something new, using language that expresses risk and innovation instead of incremental change, it creates conditions that are not great for business decision-making. This movement often starts with a single person or business within a sector, creating a sense of loneliness and risk. Our goal is to build tools, trainings, coalitions, and resources that tackle each of these challenges by consolidating information, raising awareness of the positive ROI, and creating opportunities for the coalition and community.

Tools for De-Risking

Michael Horn:

Yeah, that makes sense. So let's tackle that risk aversion one. Governments and companies are great at dropping degree requirements, but for HR, mitigating risk is important, and hiring someone with a degree just feels less risky. What do those tools look like that really de-risk this and give them the security to hire someone without a degree but with demonstrated experience?

Clayton Lord:

Well, it's a good question. Risk comes in a variety of forms. We think about the different types of risk at play, such as financial or structural risk to the organization. We're exploring ideas like de-risking the near-term financial obligation of skilling through low or no-interest loans, mini-grants, and consortium models. We've done this in some of our pilots, providing seed money for interventions, which boosts success rates.

Skills-first hiring and advancement are already happening under the proxy of a degree. Every person is ultimately hired for their skills. The current model doesn't allow time to take in the fullness of a person's skills and aptitudes, often reducing a resume to a six-second glance. Technologies are being developed to parse resumes and experiences into skill stacks, matching them with job requirements. This technology allows a candidate to progress to an interview based on their skill stack rather than their degree.

Another risk is personal risk. If a candidacy fails, sometimes the blame is on the candidate, and sometimes on the person who picked them. Over time, we need to deal with this reality. We've identified two main strategies. First, we lack great case studies of skills-first hiring and advancement strategies demonstrating positive ROI. We're working with the Business Roundtable and the US Chamber of Commerce Foundation to create a compendium of diverse case studies. Second, we're investing at the individual level, working with Opportunity at Work and other partners to create a credential for skills-first hiring and advancement for HR professionals, hiring managers, and C-suite decision-makers.

This credential will provide documented expertise, supporting dialogues with decision-makers and boosting confidence in one's ability to implement skills-first practices. The Skills-First Center of Excellence, coming online at the beginning of 2025, will organize resources, provide direct information, and offer certification for skills-first hiring and advancement professionals.

Understanding and Communicating Skill Requirements

Michael Horn:

Makes a lot of sense. You've actually answered a bunch of the other questions I had. Let me ask this one, because it strikes me as a bigger question mark. Employers often don't know the skills at the heart of successful employees. They might know the technical skills, but job descriptions are almost more legal documents to mitigate risk, listing every possible skill. How do we move to skills-based hiring if employers don't understand what the skills should be?

Clayton Lord:

It's a fair question. People use degrees as a proxy for much more than they're actually for. They're doing this because they don't know how to write an accurate job description that reflects the full spectrum of what someone will do. Most job descriptions include core tasks and a catch-all "other duties as assigned."

When advocating for employers to shift from degrees to skills, we ask them to consider what it takes to adequately and accurately describe what a person needs to do to succeed at work. This involves more than just hard skills. Employers often say they can train most hard skills into someone. What they look for is a specific combination of durable skills, plus a desire, aptitude, and positive attitude for the work.

We did a pilot in Arkansas, and many employers said they want an enthusiastic person to show up every day, on time, and sober. They can do the rest. Degrees as a proxy are an unfair way to start that conversation.

There are emerging technologies that help. For example, tools using AI to pull skill stacks from resumes and job descriptions, matching them together, and proposing candidates based on these matches. This allows hiring managers to stay within their comfort zone while expanding the pool of candidates.

Indicators of Success

Michael Horn:

Got it. That makes sense. Last question as we wrap up. In a decade, if you meet your goals, what are the big indicators that will show we've reached this vision of a skills-first hiring environment?

Clayton Lord:

The biggest indicator will be if skills-first hiring is ubiquitous and unremarkable, the default practice. It will be an exception if degrees are in job requirements or if applicant tracking systems lock people out without a degree.

We'll see workplaces with more fluidity between jobs, reflecting SHRM's own experience. At SHRM, we've simplified job descriptions to focus on core skills, allowing broader engagement and fluid movement within roles. This is essential as work becomes more intersectional and evolutionary.

We'll also have our hard metrics: 100,000 employers and 500,000 individuals involved in skills-first hiring. We estimate that skills-first hires, moving from non-degree to degree-equivalent tracks, could result in an average of $26,000 more per year in income, $900,000 more over a lifetime. This would benefit populations historically disadvantaged by degree requirements.

Given the decline in two-year and four-year degree attainment, we need to change or face a significant worker shortage. Some industries are already in crisis due to degree requirements, and they're the most open to skills-first innovation. Our goal is to be proactive, helping the world of work adapt before every industry reaches a crisis point.

Michael Horn:

When the alternative is no human talent at all, employers realize there's a lot of human talent on the sidelines. Let's unleash that talent. Clay, thank you so much for your work in moving companies toward these practices and for unleashing the potential of many who would otherwise be sidelined.

Clayton Lord:

Thank you for having me. This has been a great conversation.

The Future of Education is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit michaelbhorn.substack.com/subscribe