Oct 15 2024 7 mins

In my very long mailing list—which this platform insists on distributing a newsletter instead of leaving the reader alone at his own free will—I also have writers whom I admire. One of them, Antonio Muñoz Molina, a well-known Spanish novelist and columnist, wrote last month in El País that he is fed up with unsolicited emails.

Twenty years ago, in the early days of the blogosphere, there was no newsletter at all. If one wanted to add the blog he loves to read as a bookmark in his browser, he just did it, instead of this nuisance of a newsletter that equals targeting the craft of a prolific author along with all the pounding commercials written by a robot that clog everybody’s email inbox.

I write between five and seven thousand words a day, given that I am a graphomaniac. I use most of them for my manuscripts-in-progress, of course. But I also devote a small part of my output to other needs, that is, journaling, correspondence, and finally these installments, where I always try to be as succinct as possible. The reality is that I cannot help myself; I love pounding away at my keyboard, as a virtuoso pianist does, and it’s the life I choose, at tremendous personal cost, since being a fiction writer leads to giving up a lot of things, like raising children and the kind of security that makes ordinary people happy.

Precisely for this reason, when this author whom I always admired so much once gave me immense joy when he was kind enough to respond to me with a few lines. Since then, I’ve dubbed him “Maestro” because his disarming humility hid an astounding literary talent.

I wrote to him a long mail in one of the darkest times of my life, sixteen years ago, when I tried to keep the warrior's morale afloat amid rejections. I had lost the silent company of my books, then stored in boxes, and took one plane after another, with no direction home, embracing the kindness of strangers, and scribbling furiously a medieval trilogy.

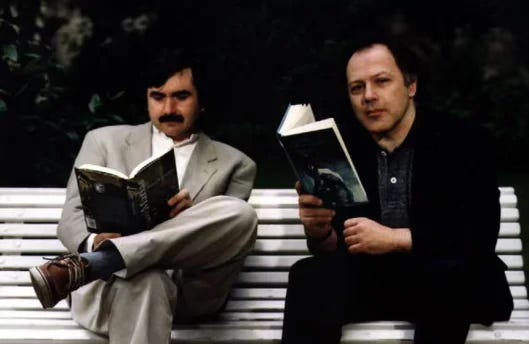

I told him I was a whole acrobat. In fact, I had more lives than a cat and incredibly always managed to land on my feet, convinced that I was within an inch of achieving a sparkling destiny like his. Not for nothing, Antonio Muñoz Molina is considered by broad consensus, even among those who envy him the most, the best Spanish writer alive. Reading any of his texts out loud literally gives me chills, an unequivocal sign of being channeling a whole Mozart unleashed. No matter how much trade I have as a narrator, I am not immune to what I read, and I have to settle down, take a deep breath, and try not to break my voice.

I also wrote about a blog that by then he was writing from New York, where he was residing for several years, giving master classes at Columbia University. He had written about one of the greatest moments in English literature, which was the second part of Virginia Woolf’s novel, To the Lighthouse, titled “Time Passes.”

I can’t quote that long mail I wrote to him, as I lost everything when I melted the MacBook I had at the time, an occupational hazard. However, I believe it had sufficient punch for such a living legend to dedicate his attention to me. What he wrote to me, I have never forgotten.

He wrote back saying that what I had said about me reminded him a lot of his days as a civil servant in Granada, where he was organizing jazz festivals, when he submitted his manuscripts for literary awards and no one paid the slightest attention to him.

Until one day, like a surreal fairy tale, a friend of his left a booklet of press articles for the literary director of the very same publishing house Seix-Barral, Pere Gimferrer, known also as an exquisite poet in his heyday and a prestigious scout, who was passing through to give a conference.

Nine years later, Antonio Muñoz Molina became the younger academic and had already won a lot of accolades for his novels. He was a notorious dark horse.

That's why I had to keep writing, he told me, and stay impermeable to despondency. Virginia Woolf, he added, did not have the slightest idea in her day that we would all be celebrating her a century later, because she was quite busy and perhaps very worried that her hand would stiffen and the pen would fall to the ground, in one of those dizzy spells that the poor woman had and that she was so much impaired.

Perhaps it serves as a finale to describe the night before I got married, when my eccentric bachelor party consisted of attending a talk by the Maestro about his latest book,To Walk Alone in the Crowd, in the forum of a modern library, which I went with my partner in life. It was the last night of February 2018, the tail end of that winter; heavy rainfall, freezing temperatures, and a snowfall forecast. As there was hardly any room among so many readers, we had to climb a lot of stairs to find a place in the last row, something that Melissa hates because of her wobbly feet. After the introduction by the editor, Antonio appeared wearing a cardigan and corduroy pants, nothing fancy, almost apologizing for so many people turning out that they had to squeeze in. My original plan was to ask for the blessing of the adventure that began the next day. But after a while, I knew that with such an audience, raging to get an autograph in the copy they carried with them, it would be mission impossible. So I had to settle for seeing him talk to the presenter about an experimental book that he had come up with while walking down the street, recording casual scraps of conversation with his iPhone, and making collages with press ads in his notebook, like a child playing.

Get full access to Don't You Dare To Think Out Loud! at javiertruben.substack.com/subscribe